London, May 1st 1851 – The Crystal Palace opened its doors to welcome thousands of visitors to the first Universal Exhibition – a state sponsored showcase of cultural, industrial and technological developments, and extracted and processed resources. Among their pavilion’s offerings, the British Empire boasted a series of new machines to aid in the rapid expansion of factory production and, exhibited among the machines, the workers whose labour was fundamental to their operation. In contrast, the American pavilion, while showcasing the wealth of their nation, offered no trace of the enslaved labour used in the production and generation of that wealth. In protest of this glaring omission, an abolitionist group staged a protest action. At the heart of the action were “fugitives” Ellen and William Craft who, in 1848, had escaped largely thanks to Ellen’s ability to pass as a white man.

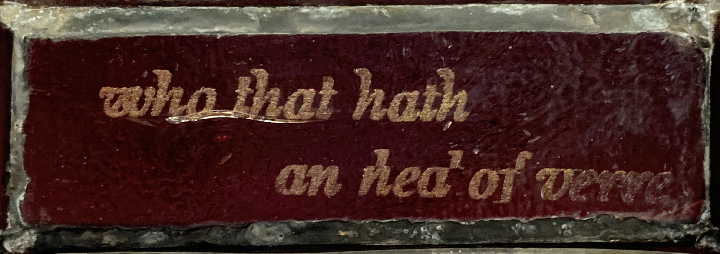

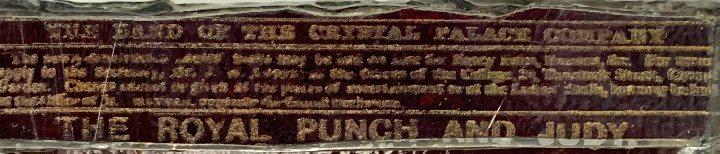

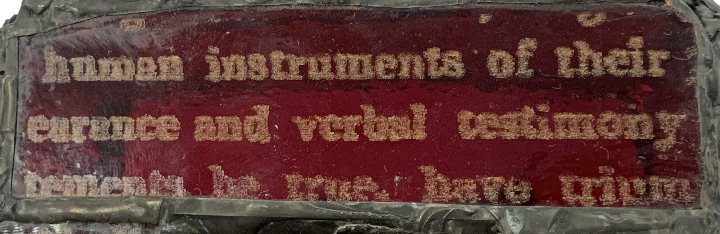

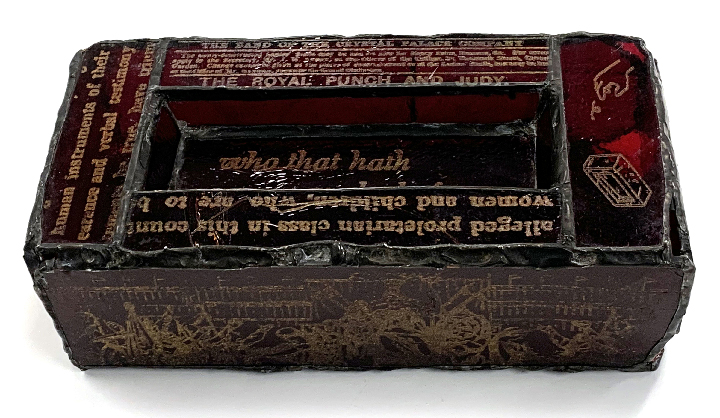

This work, a brick made of glass and adorned mostly with details from archival publications (The Liberator, The Builder, Punch), highlights a network of interconnected histories to shed light on the hypocrisies of empires and the way its systems – economic, political, social, cultural – continue to reverberate in contemporary experiences of structural violence.

This is the first in a new series of sculptures which use the history of glass architecture as a portal to explore the persistent realities and material conditions of imperialist power, the fragility of political supremacies, and the deceptions and contradictions of modern liberal political thought.